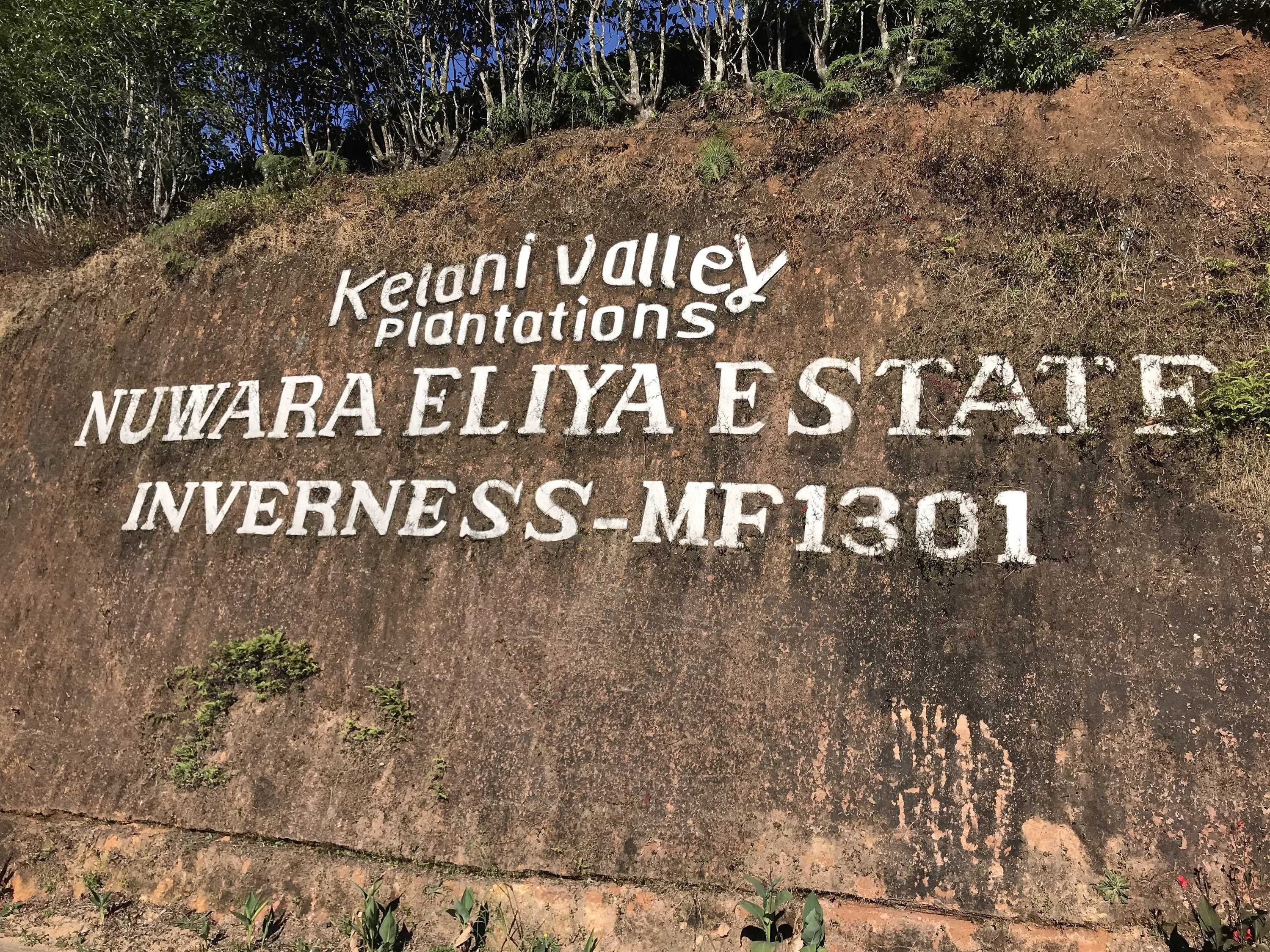

How did tea conquer the world? What shall we know about the tea plantations of Sri Lanka and tea leaves production? A view of the legendary high-growing plantations. More specifically, we talk about Sri Lanka, but somehow Ceylon and tea has been so confluted since centuries. While visiting the country, beyond elephants and cultural and historical attractions, I expected so much to see Sri Lanka’s legendary tea plantations. On my way to Nuwara Eliya, to the 1,900-meter-high mountain through the serpentines, I was amazed by the giant inscriptions. They looked like the American Hollywood signs, on which the names of the plantations were meant to be presented. This western feeling intensified upon arrival to the city as I saw the many colonial buildings (Little England). These highland settlements were once popular residences of the colonizing Britons, thanks to the pleasant mountain climate. But not only did the city inherit the many brick houses and western architecture, but also the English gave birth to the tea-growing, which is still Sri Lanka’s main source of income.

The history of Ceylon tea dates back to the 1860s, when an enterprising coffee planter named James Taylor, from India, brought some tea shrub seeds and he began experimenting on the sunny mountains of Sri Lanka. The tea shrubs proved so viable on the slopes of Loolecondera that they are still produced here to this day together with more than 1,000 tea plants. But the world’s success would not have been possible without the involvement of Sir Thomas Lipton, who visited the island in 1890 and began selling high-quality tea in Europe and in America in 1890. Quality has made its way, and the rest is history.

Sri Lanka has maintained its leading role in the world tea market ever since. With a production of around 307 million kg per year, it is considered the fourth largest exporter of tea in the world, and roughly one in four tea sold on the global market comes from here. In Sri Lanka, tea cultivation can be divided into six main regions (Nuwara Eliya, Dimbula, Kandy Uda Pussellawa, Uva and the southern province), which are distinguished between low (610m), medium (between 610m – 1200m) or high-grown (over 1200 m) plantations. The higher the place of the tea plantation is, the more valuable it is.

Nuwara Eliya, where I spent a lovely day, is a gem of tea growing in Sri Lanka with a height of 1900 meters. At one of the oldest tea processing plants in the country (Glenloch, 1917), a lady wearing a beautiful sari introduced us to the mysteries of tea making. After that, we made a short walk on the plantation where we met the women working in the tea fields. In fact, tea leaves are mainly taken by women, every day of the year, for about 12 hours a day. Most of the time, girls follow their mothers and grandparents to learn the basics of the profession: how to walk down the steep hillside between the bushes, how to clip the leaves, which otherwise renew every seven days, how to collect minimum of 16 kg leaves into the bag on your back and carry it to the factory. It’s really hard work and knowing how ridiculously low the salary that women get for this work ($4-7 a day) it gives you even more appreciation of your own situation and life.

Tea manufacturing is a very interesting process that we gained an insight into it during our factory visit. The first and most important step is to have the right leaves taken. This means the top two leaves on the branches of the tea shrub, with fresh leaves in the middle to be opened.

When, at the end of the day, women take back the bag filled up with the tea leaves (16-20 kg), the quantity is measured firstly. Then the leaves are placed on a large tray in a well-ventilated room, where they dry for about one day, while the moisture content disappears by approximately by two-third. The slightly wilted and already rattled leaves are then swept into a drain-like funnel, then shaken on a mechanized tray, which shatters the cell structure of the leaf and releases enzymes. The smashed leaves are left standing in a fermentation room for about 30 minutes, where enzymes interact with air saturated with water vapor.

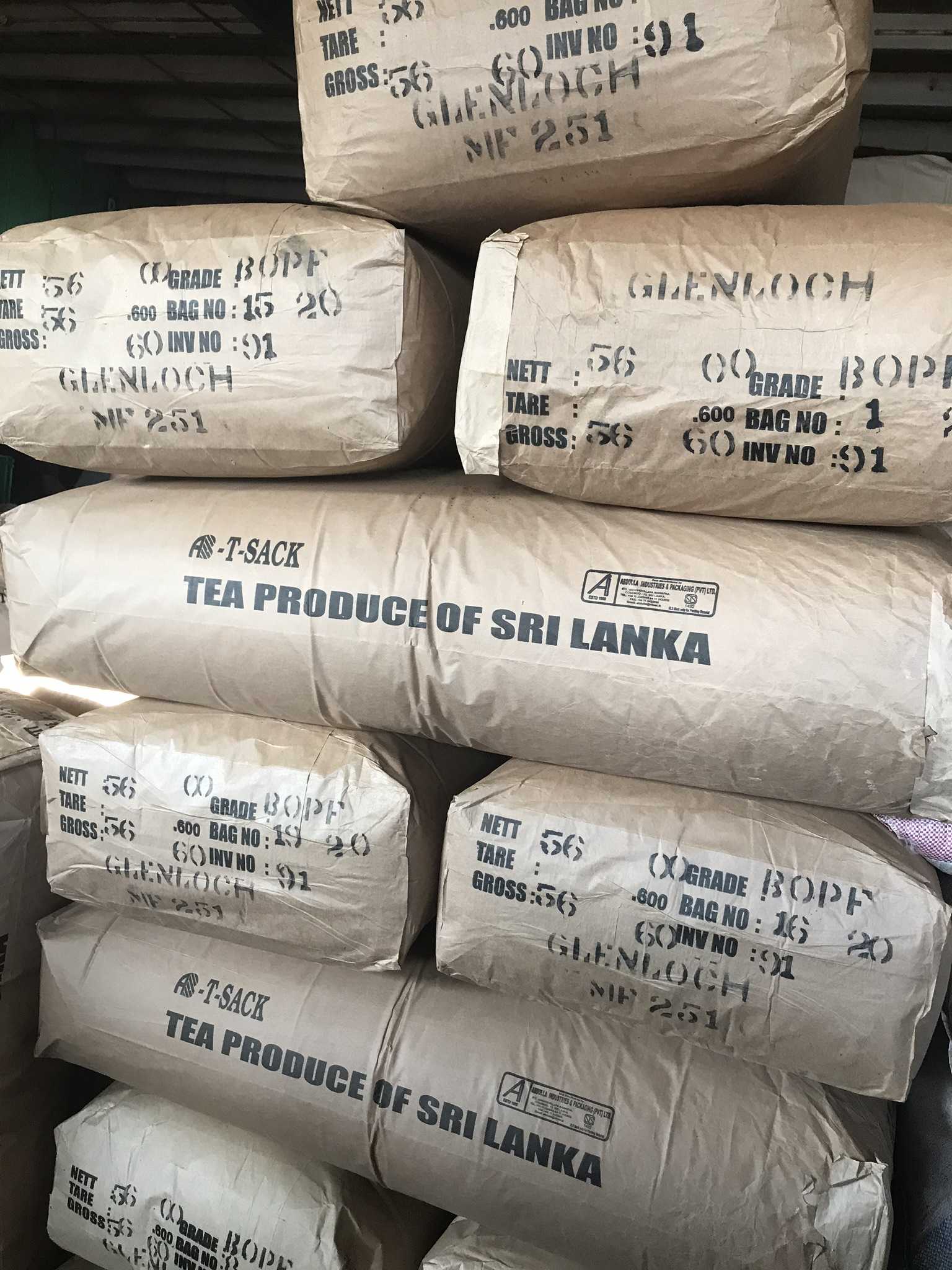

Then the leaf debris is placed in an oven, which, by heating, prevents further interactions and chemical processes. Getting out of the oven, the leaves shrink, blacken and the room is permeated by the delicate smell of black tea. It’s interesting that raw tea leaves don’t smell like tea, just after processing. Coming out of the oven, the end product is classified by taste and strength and goes into the 50 kg bags. From there, in a filter or in fibrous form, the Ceylon tea gets to the shelves of the shops in more than 28 different forms (e.g. BOP, BOPF, OP, Pekoe) and serve out all the consumer’s needs in the whole world.

The most valuable one is the silver tip, that is, the white teas, which contain only the middle, unfolded leaves. It’s usually taken in the early hours of the morning, before sunrise, ensuring perfect freshness. The operation requires special expertise, leaves should not be broken during picking, as this would cause the loss of its unique flavor. While tea plantation workers can take down 16-20 kg of leaves per day, silvertip pickers can collect only 200-250g of sprouts per day. Therefore, the price of silvertip teas is quite high, 80 gr of leaves costs about 10$. Green tea, unlike white, already contains the bottom two leaves, which are rolled together before drying and can enter the oven and later for classification. BOPF and BOP teas are the ones you most often encounter as consumers on store shelves in filter versions. If you want to buy high-quality tea, which is guaranteed to come from Sri Lanka and meets the highest quality standards, then look for the winged lion with a drawn sword in hand on the packaging, as it is a trademark of the original Ceylon tea.