When I traveled to Krakow, I knew I wanted to see the former concentration camps: Auschwitz and Birkenau. I knew it wasn’t going to be a good experience, but for once in my life, I thought I’d have to do that. I thought before I left my home that I won’t write about it. I’m not involved. Do I even have the right to write about something I don’t have a direct connection to? After I came home and a few days passed, I decided to write this story anyway. If I didn’t write it, I’d have the feeling I stick my head in the sand. However, over an organized genocide, a man cannot turn a blind eye and bury his head in the sand. Whether it’s the North American Indians, the concentration camps of World War II, the Stalin dictatorship, the Rwandan or the Armenian genocydium (in this context I suggest watching The Promise movie), almost every nation has its own deads. People who have died a violent death in the name of an ideological, religious, territorial, or ethnic idea. And unfortunately, the use of past tense is far from correct.

It’s October, a cold, hot autumn morning. We arrived in Oswiecim, an abandoned country town. We get off the train and we’re silently sauntering down the streets to the entrance of the camp. Since there is no luggage storage at the station, we pull our rolling suitcases for 1.5 km. We hardly meet anyone on the way. All the buildings are abandoned and depressingly ruined. Time really stopped here. Everything stayed the way it did many years ago. In some places, there are a pair of rails by the side of the road. Most of it has already been overgrown by weeds. Nature is good at hiding the dark secrets of the past. When we finally got to the camp, we put our bags down. We’re going on a 3.5-hour guided tour of English and get to know the darkest hours of humanity. The life-and-death fight from which the latter came out victorious. After the German occupation of Poland in 1939, the former Polish garrison was deported to Oswiecim, known as Auschwitz I, at the behest of SS General Heinrich Himmler. Initially, only Poles were brought to the camp, and later Soviet and Jewish prisoners followed them. Above the entrance to the gate, Arbeit macht frei (work sets you free) welcomes the arrivals, who were greeted by hard work and brutality. In October 1941, 10,000 people lived in barracks 1-3, 12-14, 22-24 as prisoners. In the middle of an extremely cold winter (- 40 degrees), malnutrition and continuous executions, in just five months, 9,000 people died in Auschwitz I. Every morning and evening, SS soldiers held mandatory roll call readings at the camp. As the number of arriving inmates constantly increased, the number of prisoners increased, and the inspection took longer and longer.

Most people couldn’t stand in the row for hours in snow and frost. Sick and exhausted prisoners were dragged out of line by soldiers, publicly flogged, or simply shot down. The camp was surrounded by barbed wire from all sides, it was impossible to escape. Those who succeeded, but were later caught, were expected to suffer cruel retribution and public hanging. Many, in their final desperation, ran into the electricity-powered fence.

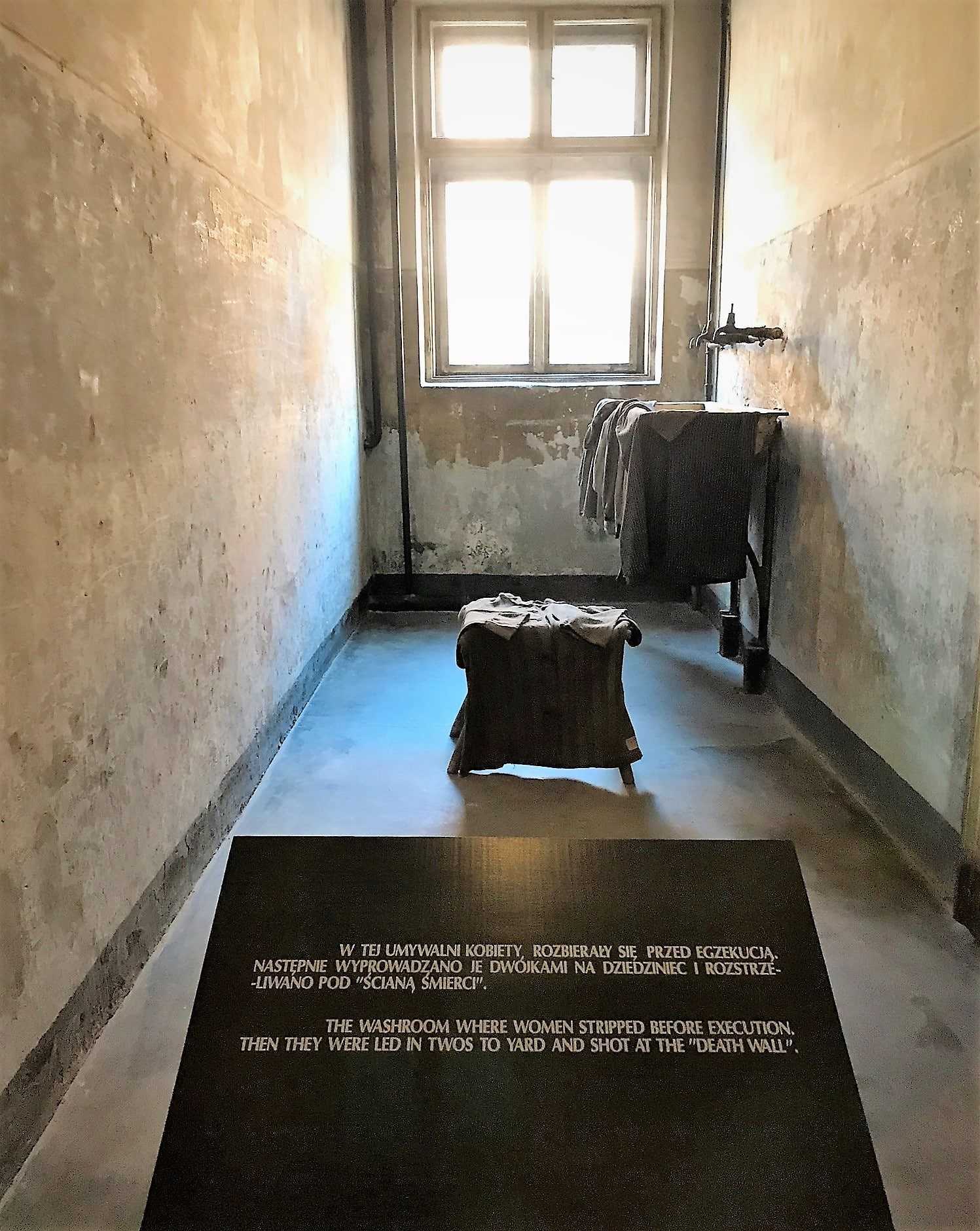

There was no turning back from barracks number 11 reserved for the death row inmates. From the airless and windowless cells in the basement, it was not possible to see the courtyard fortunately, that served as an execution place. 5,000 mostly Polish and Soviet prisoners died in this court, the Germans’ line fire. The death wall was demolished by the Germans in 1944 but later restored in memory of the victims. This is what it looks like today.  In 1941, the Germans began building another camp called Auschitz II, 3 km from the first. By this time, Polish residents living in the small village of Brzezinka (German: Birkenau) had already been exorcised from their homes by the soldiers. All obstacles to build a new camp in the name of Nazi ideas to solving the Jewish issue were disclaimed. Nearly 1.1 million Jews were deported to the camp in Birkenau, most of them, 430,000 from Hungary. The camp was originally designed to accommodate 100,000 people, but by 1942 that number had doubled. Jews who were registered fit to work lived in these barracks, men and women separately from each other. Children were kept in separate locations, often for experimental purposes. Even 700 people were crammed into the dark houses, housed in beds on three storeys. Hygiene conditions were extremely poor. For a long time there was no toilet or running water, so after the appearance of the rats, the plague quickly appeared in the camp.

In 1941, the Germans began building another camp called Auschitz II, 3 km from the first. By this time, Polish residents living in the small village of Brzezinka (German: Birkenau) had already been exorcised from their homes by the soldiers. All obstacles to build a new camp in the name of Nazi ideas to solving the Jewish issue were disclaimed. Nearly 1.1 million Jews were deported to the camp in Birkenau, most of them, 430,000 from Hungary. The camp was originally designed to accommodate 100,000 people, but by 1942 that number had doubled. Jews who were registered fit to work lived in these barracks, men and women separately from each other. Children were kept in separate locations, often for experimental purposes. Even 700 people were crammed into the dark houses, housed in beds on three storeys. Hygiene conditions were extremely poor. For a long time there was no toilet or running water, so after the appearance of the rats, the plague quickly appeared in the camp.

A special train took mainly Jews (later Roma, Soviets and Poles) arrived at the camp several times a day. When they got off the wagon, people left their luggage behind the tracks, and then the selection process officially began. An SS doctor showed up, waving a right or left-hand signal to decide who was fit to work and who wasn’t. He was the master of life and death within the camp. Women and children were separated from the men after landing. It was the last time many families saw each other alive. Those who were declared fit for work (25%), were moved to the barracks and the others were led to the gas chambers. To avoid the panic, people were told they’d take them to the shower. Even showerheads were installed on the walls of the chambers so no one suspected what was going to happen. Of course, after a while, they knew, since the selection process was repeated three or four times a day as more wagons arrived in the camp. In addition, personal belongings, suitcases, clothes, cut-off hair, gold teeth and jewelry of the deceased were seized by living prisoners in the so-called Canada houses. For reasons of grace, I do not post pictures of the exhibited belongings. Bodies from the gas chambers were burned in crematoriums II and III in Birkenau. Their ashes were scattered in the lake next to the buildings and the Vistula River. It is said that among the ruins of crematoriums, to this day there are signs of human ashes. As the end of World War II approached, Germans burned almost everything behind them in Birkenau and Auschwitz. They were trying to cover up the trach of the institutionalized killing. But the past does not forget.

*****

It’s October 31st. It’s a very mild autumn day of the season. This time a week ago, I was in Auschwitz and Birkenau. I stop for a second. I’m soaking my lungs full of fresh air. Meanwhile, I can feel the warm rays of the sun on my skin. Soon it is all soul’s day. People light candles and remember on their deceased loved ones. This year, I’m going to light an extra candle. In memory of the dead resting in the world’s largest (Hungarian) cemetery.